Dr. Kathrin Loer – who leads a research project on political strategies influencing individual behavior – investigates which policy instruments policy makers opt for to fight obesity in the US and under which circumstances. How can we explain the specific ways to deal with an extraordinarily complex policy problem? The US case reveals that a problem with diverse causes like obesity needs specific, sustainable and especially “culturally-tailored” interventions to tackle such a challenge. These insights can be instructive for North Rhine-Westphalia where the number of people with obesity and overweight is increasing.

At first sight it might sound strange to deal with obesity from a public policy perspective. There are, however, three reasons why it is worth having a closer look at this phenomenon, undertaking a deep dive by means of a policy-analysis. Firstly, obesity is or will become a severe societal problem with major effects on individual people affected, as well as society and the economy as a whole. Secondly, obesity is connected to several fields of policy-making, with many diverse actors involved and difficult political decisions to make – therefore, it can not only be read as one example under similar types of complex policy problems, which challenge public policy specifically and continually, but should also be embedded into discourses about consumer and economic policy, which is often overseen.

Obesity as a policy problem: Managing complexity or solving the problem?

On the (missing) interconnectedness between food, health and consumer policies in the United States

Author

Dr. Kathrin Loer researches public policy with a special focus on policy instruments. In her current research project (2017-2020) she studies political strategies that try to influence individual behavior (e.g., in (public) health, environmental policy, and consumer policy). She is particularly interested in the role that behavioral sciences play in public policy. She wrote extensively about policy instruments and developed a concept on how to understand behavioral public policies. Loer also researches public policy in a broader sense, especially with regard to stakeholder interests and external effects on policymaking.

1. Introduction and public policy framework

At first sight it might sound strange to deal with obesity from a public policy perspective. There are, however, three reasons why it is worth having a closer look at this phenomenon, undertaking a deep dive by means of a policy-analysis. Firstly, obesity is or will become a severe societal problem with major effects on individual people affected, as well as society and the economy as a whole. Secondly, obesity is connected to several fields of policy-making, with many diverse actors involved and difficult political decisions to make – therefore, it can not only be read as one example under similar types of complex policy problems, which challenge public policy specifically and continually, but should also be embedded into discourses about consumer and economic policy, which is often overseen. Thirdly, the phenomenon of obesity is up until now predominantly researched in and with regard to public health although its characteristics also ask for political research, which uses different concepts and methods in order to highlight the significance of the “political” that is inherent within the phenomenon. Generally speaking, “fighting obesity” as a political task means to develop political strategies, it means to decide upon political instruments that should address target groups as effectively as possible and that simultaneously acknowledge key elements of free societies and markets, which citizens and market actors typically adhere to.

Not only with regard to obesity prevention, but also in various other fields of public policy, there is an overriding need to adequately address certain target groups. Furthermore, policy-makers have to choose and design tools that balance out the claims of the citizens, who on the one hand want to live in a free society and who are accustomed to use and enjoy all goods and services that a free market economy has to offer, while these citizens, on the other hand, wish for consumer protection, if needed. Summing up, this situation could end up in a dilemma as it is all too easy to imagine a very loud cry of protest, if certain popular goods were to be forbidden or certain routines were to be strictly regulated e.g. how fast to drive a car or what to eat – especially in Germany. We can also imagine a similarly loud cry in cases of food or product scandals.

However, citizens typically wish to be protected in cases where goods and services might harm their health or even their life. There are a number of obvious cases in which citizens expect the government to consider protective measures or to introduce effective regulation in order to reduce danger – be it a certain ingredient in food, procedures how to produce certain goods or possibly dangerous products that people are in contact with (cosmetics, cleaning products, air pollution etc.). Although, things are getting difficult with regard to respecting individual demands and ideas, while trying to answer the question how far and intrusive governmental regulation should be. Governments have to consider how to protect their people or what goods and service are regarded as being harmful or risky and who should be protected and how (e.g. age groups, people at risk etc.).

Interestingly enough, there are also goods and services, that are – to a certain degree – not harmful, but could harm people’s health, whenever they are consumed too intensely or used more than is advisable. “Die Dosis macht das Gift” is a famous German phrase, to put it in a nutshell. Most of these things (food, drinks, pleasures provoking sedentary behaviour etc.) can affect human beings and their health differently, since people are diverse regarding their metabolism, personal situation, other lifestyle factors etc. Against this background it is extremely difficult and challenging for policy-makers to act, especially when they are also confronted with the interests of market actors (industry, agriculture, providers etc.) who offer such goods and services and base their business on the sales thereof – although these goods could be classified as being risky or harmful under certain circumstances.

When it comes to so-called non-communicable diseases (NCDs) we can observe an increase in attention being given in public policymaking, which leads to policies aimed at reducing the increasing number of people being overweight or obese, because obesity is claimed as being one of the major factors for NCDs. Policy-makers are alarmed because of a variety of effects that the issue of obesity is producing when causing NCDs: rising costs in the health care sector, consequences regarding productivity and labour market participation and effects regarding infrastructure. However, how policy-makers deal with NCD prevention and especially the problem of obesity, highly depends on the way obesity is put on the political agenda.

Obesity as a policy problem provokes the question how policy-makers frame and address a problem that looks like a health problem but includes many facets beyond it. Research in the US should answer the following questions: Which political instruments are policy makers opting for? Under which political circumstances? How can we explain the specific ways to deal with an extraordinarily complex policy problem? This report will present results from research undertaken in the United States (US) where different developments and approaches can be observed on federal and on state level – which gives some insights that could be instructive for federal states in Germany, especially for North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW).1 The prevalence of obesity in the US is extremely high and there is a long history of public policies addressing people that are obese or at risk of becoming obese. This report starts with an overview of how the phenomenon of obesity can be linked to debates in public policy and which conceptual framework will be used to analyze policy approaches. The next step characterizes the problem structure in the US and gives an overview of figures from different states. With this background this research report presents first analytical results found with regard to the portfolio of policy instruments which are relevant in the context of obesity policies and which are up for debate in US politics on federal and state level.

1.1. Public policy and the question how people do what they are supposed to do

Policy-makers regularly address individual citizens in several fields of policy-making, such as in consumer policy, health policy, climate policy, environmental policy, traffic policy. First and foremost, they do this in order to fulfill the state’s duty to protect its citizens, whether from the risks of specific products, specific diseases, environmental pollution or traffic accidents. This is the “classical” field of policies designed to protect consumers and their well-being. In addition, policy-makers address individuals when citizens are (made) responsible for certain decisions and their consequences.

If such consequences are to be avoided, or at least mitigated, and if specific political aims are to be achieved, then governments need their citizens to behave in certain ways. By addressing the individual, policy-makers seek to elicit compliant behaviors and they need to “fashion an instrument that will work in a desired manner” (Linder and Peters 1984: 253). Taking this as a starting point, managing complexity is the key to compliance because policy-makers cannot assume that all citizens are alike when it comes to their preferences and the resulting behavior. Indeed, individuals themselves are often inconsistent with regard to their own preferences and behaviors, and they often make decisions that run contrary to resolutions they have made about their own best interests (Kahneman 2011). However, managing this complexity and designing policies appropriately turns out to be extremely difficult. Not only needs the policy-taker to be conceptualized as a multidimensional actor but it is also the question who the policy-taker is. Since public policy usually requires broad-brush approaches and typically does not adopt a strategy of individualized targeting or policymaking, conceptualizing multidimensional actors challenges political actors. From a political science perspective, this leads to the question of how policy-makers deal with this challenge in order to ensure that citizens do what government wants them to do.

The case of obesity2 prevention illustrates the challenges and dilemmas that policy-makers face when it comes to choosing policy instruments. Obesity is caused by a whole host of diverse factors. It concerns the individual because it increases the risk of multiple serious chronic diseases. It also affects individual economic well-being, since he or she may not remain productive. The OECD states that “Obesity and its related conditions […] reduce GDP by per cent in OECD countries and exact a heavy toll on personal budgets, amounting to USD 360 per capita per year.” (OECD 2019). And as well as indirect costs, there are many direct costs due to the added healthcare treatments required which the individual has to bear. At a societal level, obesity has also an impact: it pushes up healthcare costs due to the range of health problems that are caused by obesity – obese people have a higher risk of “cardiometabolic diseases, osteoarthritis, dementia, depression and some types of cancers” (Blüher 2019: 289). Furthermore, specific infrastructure adaptations may be required due to heavier body weights and larger body sizes. Experts also point out that obesity is a threat to national security since a “physically qualified fighting force” becomes more and more difficult to recruit (Shugart 2016). Generally speaking, obesity is seen as a serious “contemporary concern” (Shugart 2016) for politics and societies, and it has reached the policy agenda of most industrialized countries in recent decades.

It comes as no surprise, then, that governments try to search for policy instruments which could help to reduce or at least contain the number of obese people and which could prevent children from becoming obese in particular (see Mello et al. 2006 and Musingarimi 2009). These policy instruments need to view the policy-taker as a multidimensional actor and they may also need input from scientific evidence. But besides taking scientific evidence into account, the design of policy instruments is always influenced to some extent by factors that are inherent to policy processes. First and foremost, this concerns the competing interests of different political actors as stakeholders whose voices are heard when policy instruments are debated, but also with regard to institutional factors. So far, it remains unclear how these diverging factors are impacting the way in which policy-makers handle the challenge of addressing multidimensional actors when they are choosing and developing policy instruments.

This research report draws on content and data analysis (policy reports, press releases, case studies, official responses, issue reports, guidelines, media coverage, Centers for Disease Control and Prevenion (CDC) database) and nine in-depth interviews with policy experts, researchers, non-governmental actors, and government actors.

1.2. Conceptual frame

Considering the complexity of obesity as a policy problem, it is not easy to point to a policy instrument or a mix of policy instruments that could successfully allow policy-makers to combat the phenomenon. This “insolubility” (Peters 2005: 356-358) means that the case of obesity policy can teach us much about policy-making, and particularly about choosing instruments. Peters emphasizes that policy-makers handle insoluble problems by focusing on procedure and disregarding substance, or by depoliticizing them, sometimes by delegating them to “non-majoritarian institutions” (Peters 2005: 358).

In any case, political processes are important since they guide the choice of any policy instrument which aims to prevent obesity in one way or the other – even if the choice made is simply to follow or strengthen certain procedures. Without aiming to find a “cure” or panacea, but taking this case as an inspiring example of a complex, insoluble set of political problems, the empirical examples in this article will explain what forms of political activities are adopted and show what drives policy-making in order to learn how policy-makers handle an insoluble problem.

In relation to policy instruments, the academic literature utilizes different typologies or taxonomies. In applying these typologies, scholars either aim to explain why and under which circumstances certain policy instruments are used (beginning with Salamon 1981) or use them in order to give advice to policy makers with regard to the potential effect (or effectiveness) of specific policy instruments or instrument mixes in a prescriptive way. Generally speaking, instruments are to be understood as forms of political action in a more or less technical sense if we wish to answer the question of how exactly and by what means the state does act. In relation to these forms of actions, various factors can be identified in the political process that explain the selection, design and combination of instruments. In addition, the debate on instruments in political science also addresses the question of which interdependencies there are between instruments and how political instruments evolve over the course of their implementation. Furthermore, we need to take account of how instruments develop in cases where it is up to administrations, agencies or even (private) non-governmental actors with a specific remit to design instruments in detail. But what is missing so far is how much a certain conception of policy-takers’ behavior, requirements or expectations on the policy-takers or systematic knowledge influences the choice of instruments and their subsequent evolution.

So far, instrument approaches (Béland et al. 2018, Howlett 2011, Peters 2018, Vedung, 2010) have not systematically considered how much the intended effect of the instrument relates to assumptions about the real-world behaviors of the policy-takers or whether or not this is not regarded as relevant. Furthermore, this stream of the literature on instruments does not explicitly answer the question of whether or to what extent political actors are influenced by scientific findings on policy-takers’ behavior as elaborated in behavioral science, especially regarding the reasons for non-compliance. Interestingly, most typologies do only address expectations with regard to the policy-taker in a cursory manner (except Schneider and Ingram, 1990 and Howlett 2019), and ignore the influence of behavioral sciences. If scientific advice comes into play, this could also help to depoliticize the problem (compare Peters’ argument on insoluble problems). Although we could, in principle, presuppose that all policy instruments are based on certain behavioral assumptions, the question remains of whether evidence on the most likely real-world behaviors and their interpretation is considered in policy-making. I would argue that when this does happen, it is primarily a matter of implicit assumptions which are not regarded as an essential factor when it comes to the choice of instruments.

Following the idea of a very basic instrument typology, three variants of instruments could be identified, which are clearly distinguishable from each other; however, to these we must add a fourth variant in a subsequent step. (1) Prohibitions and orders belong to the category of “authority”. These are legally regulated rules. Compliance is controlled and can be enforced by state authority – the English term “sticks” (Vedung, 2010) is revealing here. If, in our case, certain factors are identified as causing obesity, policy-makers could implement rules to target these factors – e.g. the prohibition of substances or ingredients (or the amount of certain ingredients used) in food or in drinks or an obligation to follow a certain physical activity regime, with strict controls. These examples, and variations of them, would probably provoke major political debates and therefore become highly politicized. But this instrument could also be used to complement other tools procedurally, such as informational tools (see below) in order to ensure that certain information is actually provided to consumers. If this is the case, “authority” could also be a way of focusing on procedures in order to avoid dealing with the substantive problem.

The second category (2) is constituted by incentives that are chiefly market-based, but may also be of a social nature. State actors could either use certain resources (subsidies, tax exemptions, premiums, awards) or they could impose targeted taxes on particular citizens and corporations. Incentives not only fulfil a guiding function but are also meant to steer policy-takers in a specific direction. The term “carrots” forms the counterpart to “sticks” (Vedung, 2010), and the incentivizing instrument type is also referred to as “treasure” (Hood and Margetts, 2007) or “expenditure” (Howlett, 2011). Particularly with regard to products or dietary routines that are thought to cause or exacerbate obesity, we can think of incentivizing policies designed to reduce the consumption of certain products or to promote particular lifestyles. Two broad directions are possible in order achieve an impact. Either the producers or providers are addressed, or the policy affects consumers who are obese or at risk of obesity. Since incentivizing instruments always affect policy-takers in one way or another – because certain products or goods become cheaper, economically more attractive or more expensive – they often become highly politicized. If we follow the idea that policy-makers would shift the focus to establishing a specific procedure when they have to deal with insoluble problems we could question if incentives could fulfill this aim.

The third type of instrument includes measures which have an (3) informative character in the broadest sense and which are meant to equip policy-takers with the “capacity” to make specific decisions or to behave in a certain way. Informational measures range from symbols on packaging to exhortations (without sanctions) or pure information, education and awareness-raising, all of which are meant to lead to greater understanding and/or to persuade people in a particular direction. Vedung calls this group of instruments “sermons” (resulting in: “Carrots, Sticks, and Sermons” = CSS), but these instruments are also often referred to as “information” measures. In the case of obesity, preventative informational policies appear to play an essential role, because information is required regarding preventive behavior and the (assumed) causes of obesity. Since informational policies can be designed in a variety of forms, they may lead to a high degree of politicization (for example in the case of shocking pictures). However, they may equally be used to focus on certain procedures as an empty gesture in order to (at least) take some kind of action.

The popular CSS typology explicitly excludes (4) organization and the provision of infrastructure although we do find this as a result of public policy. In a descriptive sense, certain forms of government action would not be covered by the CSS typology, such as the construction of infrastructure, the organization of round tables and forums, encouraging – through governmental activities – voluntary agreements. Hood points out that the elegant CSS typology (Vedung 2010) does not include types of policies that lead to a certain physical or environmental structure – governmental action can literally change the physical environment in which people live their lives (Hood, 2007: 140). Furthermore, in a range of policy sectors, public policy initiates, provokes or supports organizational structures or even institution building. “Organization” in a broader sense – that of organizing the elements of the physical living environment as well as organizing forms of cooperation and coordination – must be part of any typology of instruments. As far as the degree of politicization and the shift towards procedures is concerned, organizational tools could, of course, fulfill the need to establish a procedure and, in doing so, shift the focus away from actually dealing with the problem. With regard to obesity prevention, we could think of several ways of establishing such procedures but we would have to look closely to discover if they were mainly being used as a mere gesture to avoid dealing with the actual problem or if they were actually intended to promote substantive change. If policy-makers decide to build infrastructure – such as promoting physical activity by building cycle paths – this will always be an opportunity to claim the spotlight, to show to the public that they are taking action and wish to tackle a problem. This is also the case when it comes to institutionalization processes (round tables, committees etc.), but this does not necessarily attract the attention of the public. It can also be a form of establishing procedures intending to deal with the issue but without focusing on any form of solution.

What does all this mean with regard to policy-takers? Looking at the fourfold typology that I have set out, we see one typical mechanism that all these types of instruments have in common: they expect a particular and – in the broadest sense – rational response from the addressee, which corresponds directly to the stimulus. The addressee is expected to respond to the stimulus in a certain, predictable way. That stimulus may be an order, a ban, a financial incentive, the prospect of social exclusion, the desire to be socially accepted, the acceptance of a specific piece of information that leads to a particular behavior, or the opportunity to participate in collective action(s). If only these stimuli are addressed this would undoubtedly lead to raised eyebrows among behavioral scientists. Studies from behavioral science show how external influences disturb the preferences of addressees and prevent rational decision-making when they act. But research in behavioral sciences also reveals something of how the human brain works. It underlines that it is not only rationality that determines how humans make decisions, but that subconscious and non-rational factors also play a key role. Indeed, factors of heuristics and biases influence rationality and can be triggered in a way that is unintended (e.g. Kahneman and Tversky 1979). These insights help to understand why well-known policy instruments often fail to produce the intended results. Research conducted by behavioral scientists from various disciplines examines individual decision-making procedures and demonstrates how people handle decisions in different choice architectures (for an overview of tools see Reisch and Zhao 2017).

Often, in the debate on behavioral insights in public policy, the claim is made that policy-makers would now hold a new instrument in their hands. But many empirical examples show that at least one of the well-known instruments, or often a combination of two or more of them (instrument mix), are involved when a behavioral tool comes into play. What is different is that by including behavioral science insights, the mechanisms at work change and this has a major impact on policy instruments or on the political narrative that supports instrument choice. The charm or the promise of behavioral science lies in the claim that people still get to choose between two or more options; however, a bias is built into the relevant architecture of choice, of course – otherwise the use of behavioral science would not hold such appeal. If the instrument or instrument mix is re-designed on the basis of behavioral insights, the instrument or instrument mix gets a specific spin – a behavioral spin (Loer 2019) – that makes it more likely that the desired policy aim will be achieved. Applying the instrument differently could, of course, impact on the effectiveness of the relevant instrument and give it a further behavioral spin.3 As with all other instruments, there are also “coins and limits” (Hood and Margetts 2007) to the behavioral spin: obviously, the spin is only as good as the evidence that can be brought in from behavioral science. Keeping the political dimensions of instruments in mind, the behavioral spin should also be interpreted against this backdrop: insofar as political actors focus on the individual level, they might implicitly or explicitly avoid addressing corporate actors or certain types of political intervention, such as orders and prohibitions in particular.

2. Public policy view on the problem structure: Obesity on the rise

The average bodyweight of residents of industrialized countries is steadily rising: The World Health Organization (WHO) points out that the number of obese people worldwide has tripled since 1975 (WHO 2018). Public health experts explain that obesity “has increased in pandemic dimensions over the past 50 years” (Blüher 2019: 289). 42.4 % of the adults aged 20+ in the US was obese in 2017-2018 (National Obesity Monitor, https://stateofchildhoodobesity.org/monitor/, 20/05/15). Of all children and young adults between 2 and 19 years in the US, 18.5 % were obese in 2015-2016 (ibid.). What is more, in 2016 the WHO gave us reason to believe that the trend of rising obesity rates will not stop, forecasting a percentage between 40 per cent and 50 percent of the US population by 2025 – a rising trend although the global targets aim to stabilize the figures over the next decade (WHO data 2016). The continually updated figures of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation confirm this trend.

In spite of these figures, the issue of obesity has yet to be interpreted politically and could be framed differently when it comes to identifying causes and attributing responsibilities, as well as developing political options for addressing the problem. The choice of framing is closely intertwined with the question of which kind of policy instruments should be applied and how intrusive and coercive policies should ultimately be.4 Given the huge spectrum of factors that cause or contribute to obesity, actors in policy-making processes need to assess which factors to focus on in their political activities. Furthermore, political actors also need to decide who is responsible and under which circumstances. Both issues are part of the framing of the problem structure. To define an issue and its character in a specific direction determines which political conflicts may follow (Daviter 2007: 656). The question of who defines the issue depends on political resources and power and conversely, changing definitions can provoke shifts in power from one group of actors to another (Daviter 2007 following Schattschneider 1960). In the case of obesity and obesity prevention as a policy issue, we learn from the literature that it makes a difference how the problem of obesity is framed, by whom, and that case analysis should consider who the protagonists are and who the antagonists are. This is especially true with regard to the question of whether and how the individual, as a policy-taker is addressed.

2.1. A huge problem everywhere – diversity in detail

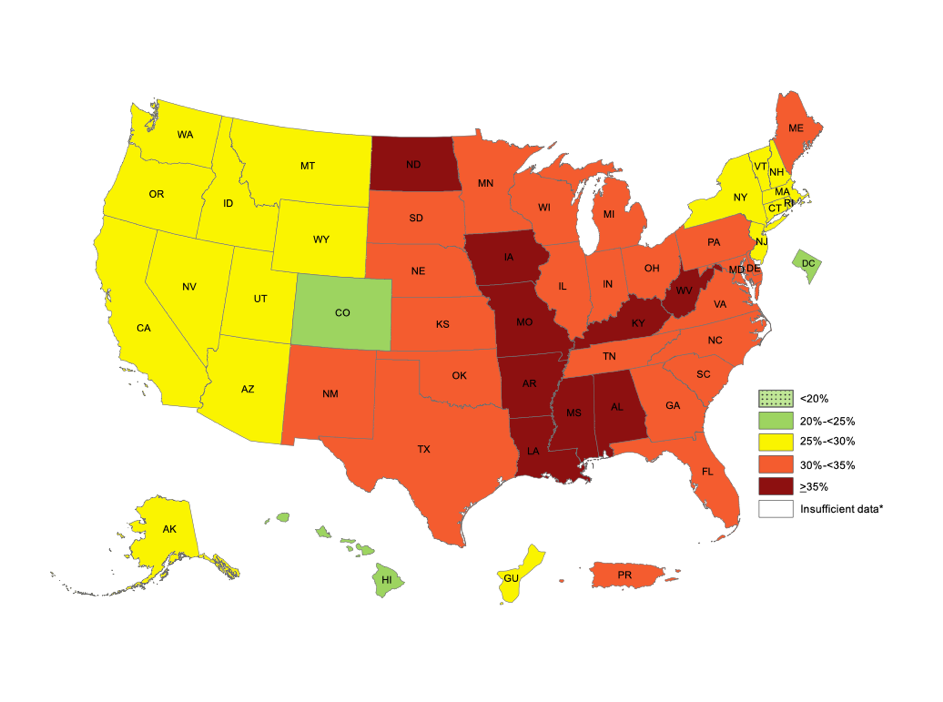

Figure 1. Overall obesity (map); Source: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html, 20/05/02

Even if the obesity rates in the US are generally high, we find diversity if we look at the state level.5 There are three states that list quite low figures: Colorado, Hawaii, and the District of Columbia. The West Coast and their neighbouring states as well as a cluster of states on the east coast (New Jersey and its Northern neighbours with the exception of Maine), Alaska and Guam (territories) are performing at the lower spectrum (25 % to 30 %). Obesity rates are above 30 % in all other states – there are nine states that even exceed the level of 35 % including West Virginia. My report will shed some light on three states each belonging to one of these four groups: Colorado (for the lowest rates), New York (low to mid), and West Virginia (high) (www.nccd.cdc.org, 20/05/02). With the exception of Colorado, the states are similar to North Rhine-Westphalia with regard to inhabitants.6

Colorado

As the state with the lowest obesity rates, 23 % of adults in Colorado suffer from obesity (2018). Despite this fact that Colorado is always highlighted as being at the bottom rank of obesity figures, even obesity rates in Colorado are continually rising from year to year (starting from 20.7 % in 2011). Adults who have an overweight classification can be found within the scope of approximately 35-36 % of the adult population. These figures are quite constant over the timespan from 2011 to 2018 (https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/data-trends-maps/index.html7, 20/05/02). Looking at youth and childhood obesity, there are rates of 10.7 % of ages 10 to 17 having obesity.

New York (State)

The state of New York reports that 27.6 % of adult people have obesity and 35.1 % were overweight in 2018 (nccd.cdc.gov, 20/05/02). Observing these figures from 2011 to 2018 we see continually rising obesity rates (starting with 25.5 % in 2011) and a quite constant rate for people being overweight (with the exception of 2012 = 37.0 % the figure is always around 35.0 %; nccd.cdc.org, 20/05/02). The Robert John Wood Johnson Foundation focusses on children and youth and highlights that “14.4% of youth ages 10 to 17 have obesity, giving New York a ranking of 25 out of 51 for this age group among all states and the District of Columbia.” (https://stateofchildhoodobesity.org/states/ny/, 20/05/02).

West Virginia

In 2011, a rate of 32.4 % of adults in West Virginia have obesity. Numbers increased and ended up at 39.5 % of the adult population in West Virginia being obese in 2018. Interestingly, overweight figures show a different trend: Starting with 36.5 % of adults who have an overweight classification in 2011 the numbers decrease to 32.5 %. (nccd.cdc.org, 20/05/02). Looking at youth ages 10 to 17, we find 20.9 % in this group have obesity (https://stateofchildhoodobesity.org/states/wv/, 20/05/02).

North Rhine-Westphalia

Data from North Rhine-Westphalia shows that obesity rates are much lower than in the US. However, numbers for NRW are steadily increasing from 14.5 % for women and 17.6 % for men in 2013 to 15.3 % (women) and 20.9 % (men) in 2015 (https://www.lzg.nrw.de/, 20/05/02). Further data from 2014/2015 shows figures of 17.4 % (women) and 19.0 % (men) being obese in NRW. We find a continuous rise if we look at data before 2013, more and more people are becoming obese over time (Kroll, Lampert 2010). This corresponds to the overall trend for Germany where we find that 18.1 % of the whole population have obesity, and 35.9 % are overweight (Schienkewitz et al 2017). The study of Schienkewitz et al. point out that the “prevalence of overweight, including obesity, increases with age, both in women and men. This observation is also consistent with previous surveys. Over time, the prevalence of obesity in particular increased significantly among younger age groups.” (Schienkewitz et al 2017, 25). Some data is available for children since bodyweight is measured in the context of an official health check which every child has to pass before school enrolment (typically at the age of five or six) (www.lgz.nrw.de/, 20/05/02): Obesity figures for girls and boys did only slightly change during the time from 2007 to 2018, however it constantly reaches the percentage of around 4 % to 4.5 % of children being obese in NRW (www.lgz.nrw.de/, 20/05/02).8

There are some indicators allowing for some hints to socio-demographic characteristics when it comes to obese or overweight people. Especially, the importance of socio-economic status seems to have a strong impact on the prevalence of obesity. A study of the Robert Koch Institute shows that the “proportion of obese persons is significantly higher in the lower status groups than in the higher status groups. Socio-economic status has a greater impact on women than on men, for whom marked differences can be seen particularly among 30 to 44-year-olds” (RKI 2015, 151).

2.2 Painting the picture – what does the specificity of the problem structure transport?

Although there is variance in obesity rates if we look at the US states presented here, there are some conclusions that apply overall: Obesity is a condition that affects a large part of the population. This is also increasingly the case in Germany as well as specifically in NRW. Interestingly, there are different trends with regard to the overweight data, at least partly some stagnation, partly decreasing figures. A spectrum of factors could be assumed that influence such a development on the meta level:

- People whose bodyweight fluctuates between normal weight and overweight manage to keep their weight below the threshold or are able to reduce their bodyweight from overweight to normal either of their own accord or with external support – such as appropriate political measures.

- The group of typically overweight people is becoming smaller in number for demographic reasons (age, migration, etc.).

- The group of typically normal-weight and underweight people is becoming larger for demographic reasons (age, migration, etc.).

CDC data is not disclosing the socio-demographic background; however, we learn from studies in public health how much socio-demographic and socioeconomic factors matter. Generally, especially minority groups and women are found to be less likely to identify individual responsibility for obesity since they do not have opportunities to change societal factors – other than men and white people (Brady 2016). Several studies show high prevalence in obesity or severe overweight with regard to non-Hispanic blacks (Wang et al 2020). Furthermore, there are disparities across ethnicities generally and also geographically: “South (32.0%) and Midwest (31.4%) had the highest rates” (Wang et al. 2020). Zenab et al. (2020) found out that “[o]verweight was more frequent in younger children, children of single parents, and children who lived in a neighborhood with no amenities. Parental attainment of college education, health insurance coverage, female gender, and language spoken in home other than Spanish were protective against overweight or obesity.” Public health studies confirm that socioeconomic factors play a decisive role and highlight poverty and unemployment, the income level, and receiving of “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program” (SNAP). If people cannot afford healthy food this may have a major impact to the increase prevalence of obesity.

Acknowledging this, we could expect policy instruments that mainly focus on socioeconomic factors, on creating a non-obesogenic environment and helping people living healthier in a sustainable way. This would mean, that policy-makers would not only have to deal with strategies in social policy, but also with regulating the market that offers cheap non-healthy food.

3. Policy instruments applied

Given the scale of the problem of obesity, it would be obvious to focus on the impact of policy instruments. However, political science analysis has clear limitations when it comes to measuring impact because this technically falls within the area of public health and medicine – and even for researchers in these disciplines it is difficult to make clear attributions of measures and effects given the complexity of influencing factors. Political science therefore focuses on the results of political processes – i.e. processes that produce specific political instruments. This research project first of all determines which policy instruments are chosen as a basis to show which political instruments are to be found at all – this in the sense of laying the foundation stone, in order to then take a look at factors that might have an impact on decision-making (which instrument is chosen why?). First answers to the question of influencing factors will be found on the basis of reports and in-depth expert interviews.

3.1. Policies on state level

This paragraph should give a short glimpse of the spectrum policies enacted in the three states, Colorado, New York (State), and West Virginia. It is based on the comprehensive data base of CDC9 which was analyzed in a first step in order to systemize the types of policy instruments enacted and strategies chosen in different states. The following sketches aim at painting a picture of fields and directions of policymaking that play a role with regard to obesity.

Colorado10

It is striking that the instrument type “organization” and “infrastructure” is chosen comprehensively. On the one hand, this involves the establishment and expansion of councils, steering committees (in the community) and task forces. On the other hand, political actors seem to devote themselves extensively to the development of infrastructure, especially bicycle paths and safe school routes are subject of political measures. Colorado also has many policies that seek to create “incentives”: taxes, grants, funding, subsidies. Interestingly, many projects that were ultimately rejected fall into this category. Presumably, most political conflicts would arise in this area, since it is ultimately a matter of taxes and financial burdens. There is no regulation of marketing and advertising. However, programmatic policies can be identified comprehensively: “encouragement in schools”, information, or even the call for schools to develop programs that aid with a healthier everyday life. Some initiatives can be found that aim to compensate for social inequality. Strict regulation, bans and orders cannot be found. As far as the main focus is concerned, a mixed picture emerges – in particular several projects in the area of “farms to schools” failed. In Colorado, no decided “behaviorally inspired policies” can be identified for the period under review, a number of initiatives on labelling were rejected (e.g. menu labelling). Front package labelling in schools has, however, been introduced.

To sum up, the spectrum of initiatives and policies in Colorado does not support the idea that food, health, and consumer policies are interconnected in a forceful, or even sustainable manner. Furthermore, there are no comprehensive programs in social policy to help individuals more than it is typically done – in the majority of policies we find that policy-makers typically address intermediaries and focus on schools and public infrastructure.

New York (State)11

The large number of policies that CDC records for New York should be seen in the light of the fact that only about 24 % of these policies entered into force or are introduced. However, a look at the policies that have been implemented reveals a complex picture: a large proportion of policies are related to agriculture and school meals. Strategies range from campaigns to raise awareness of regional agricultural products, to guidelines to initiate voluntary agreements between agriculture and schools, to sales promotion events for agricultural regional products. In addition, New York also focuses on policies that recognize and address social inequality. A notable number of programs, including those with financial resources (loans, grants, subsidies), can be subsumed under the topics “Food Assistance”, “Food Security” and “Disparities / Equities”. In addition, although New York established a range of policies in the area of infrastructure development (bicyle-paths, parks, recreation and trails, walking facilities), they account for a relatively small proportion compared to all other measures. Another group of policies are those that focus on restaurants and retail, most of them targeting disadvantaged groups (for example, in the form of incentives for supermarkets to locate in certain areas). Also worth to mention are concrete rules on standards, reformulation or as negative incentives for the consumption of unhealthy food (here: tax on sugar sweetened beverages, restrict use of trans fat). In other words, instruments from the area of more strongly intervening instrument types (bans, orders, taxes) can also be found. This catalogue of measures is supplemented by policies aimed at empowering the population and measures to set up task forces or other networks for cooperation.

Altogether, three main priorities can be identified with regard to New York: 1) The problem of socio-economic differences in the population is addressed and therefore highly relevant in policymaking. The city of New York might play a major role here due to the fact that it is a densely populated part of the state with its special socio-demographic and socio-economic structure of the urban population. 2.) On the other hand, the implementation of more binding policies (introduction of taxes, restrictions on product composition) is clearly visible. 3.) The importance of agriculture is reflected in numerous policies, which link the needs of farmers and the agricultural industry and the food supply that the global metropolis New York City needs.

West Virginia12

The total number of policies which are actually implemented in West Virginia is relatively small (compared to other states with similar population sizes). Interestingly, we find policies that deal with the budget for state administration to enable them to act – also, for example, with regard to agricultural subsidies. This form of a “financial instrument” does not clearly fall into the category of “incentives”, but rather functions as basic equipment for action in the state. In addition, policies can be identified that establish rules or binding requirements for state institutions (mostly schools) to support health-promoting behavior (including physical education). Furthermore, there are a number of policies that should be the basis for setting standards for agricultural products and foodstuffs. West Virginia also provides government support for agriculture and is involved in the promotion of agricultural products. Furthermore, there are also a limited number of policies, for example, for the development of infrastructure (bicycle paths). A few policies focus on stimulating public-private initiatives, which in turn aim to improve the physical activity of children and young people.

In sum, West Virginia seems to follow a “traditional path” with a strong focus on its agricultural industry and farmers. Little attention is paid to the issues of social inequality and to possible causes of obesity. And even if we find some more or less binding policies (that could be categorized under the headline “bans and orders”) these policies are not as intrusive as bans and orders targeting on the food industry, farmers, or the individual. Standards are addressed to West Virginia’s administrative bodies; similar attempts can be identified with regard to financial policies (budget).

3.2. General preliminary findings13

Many activities take place at state level and are covering a large spectrum of forms and levels of intervention. The extent of the problem as such (obesity rates among adults and/or children) varies from state to state, ranging from Colorado where the lowest obesity rates are registered to West Virginia ranking on top of the list. But even if the figures are diverse, the problem as such can be found in all states – and even in Colorado we observe rising figures. The overview of four states (as illustrative examples) show that there are multitudinous activities to be observed: a broad use of informational and organizational tools at all political levels, legislative acts at state and federal level and economic incentives on state level. The majority of activities can be characterized as “informational” or “organizational”. The instruments address intermediaries, such as teachers, educators, nurseries, health professionals etc. School-based and early childcare educational approaches dominate the picture. There are also varieties of programs that seek to increase public awareness. A great number of activities aim at provisioning “tool kits” and fact sheets – in a more or less detailed form these tools focus mainly on teachers and educators, sometimes also parents, in order to help them, not only informing children and young adults about healthy behaviors (diet and physical activities), but also in order to establish standards and procedures which should be followed in public and private institutions. We also find policies which specifically entail investments for building environment, planning resources and stimulating cooperation. These activities are mostly concentrated on promoting physical activities or helping to provide for a daily supply of fresh products (supermarkets, grocery store) in regions where such an infrastructure is lacking (so-called “food deserts”). Generally, there is a very strong focus on street level bureaucrats, teachers, health practitioners and professionals as policy-takers who could be in contact with obese people (and parents of obese children) or societal groups that are on the edge of becoming obese. In addition to all these policies, which can be classified as either “informational” or “organizational”, more coercive policies can be found. Many states apply policies that are closely related to the specifics of the U.S. school system. In about half the states we find legislation that sets standards for school food and beverages, such as nutritional standards. Furthermore, there are requirements for physical education in place that vary, but which are in some cases claimed not to be enforced effectively. Assessments and evaluation such as screenings (BMI) are executed in more than one third of the US states. In addition, we find several attempts to introduce taxes on soda beverages and to enact menu labelling as a rule. Both interventions are highly disputed and under attack by industry lobbyists – this led to activities in several states whose governments pre-empt their cities from taxing soda beverages. Nonetheless, we could observe sugary-drink taxes being in place at a local level (Albany, Seattle, Philadelphia).

At federal level we see several programs and activities whose impact partly changed after 2017 – this is especially the case for all policies that are interlinked with social supporting systems, such as Food Stamp Access (FSA) or the Supplement Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) whose budgets were cut. Before 2017, we found a spectrum of policies acknowledging health inequalities and considering the issue of healthy nutrition specifically. Regardless of these changes, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) sets regulations and nutrition standards that are to be followed by the states, but which could also be exceeded.

In the US we observe a) that policy advisors reflected and conceptualized how the policy-takers would probably behave; but such advice does not regularly affect or impact governmental policies, particularly at the federal level. The picture at state level is multifaceted. At state and local levels lots of activities (partly) reflect the limits of approaches that focus on the individual. Instead, there are policies showing that policy-makers acknowledge the need for rebuilding the social environment. In this regard there is a major role for governmental, but especially for non-governmental actors: universities, non-profit organizations and private actors. b) Insights from scientific disciplines play a role, but mainly on a descriptive level. Behavioral insights do not stand out, there is also no visible expert unit of behavioral experts promoting specific tools or approaches with regard to obesity prevention after the Social and Behavioral Science Team (SBST) was converted to the Office of Evaluation Sciences (OES). US obesity policy tends to support Peters’ assumption of “de-politicization”. We do also see a shift towards establishing procedures instead of handling the problem. Especially during the years after 2017, obesity as a policy issue cannot be found at high political levels or in the official political discourse in the same way as it was before 2017. Furthermore, different attempts from the government’s side (federal and state level) would support the assumption that the problem is supposed be de-politicized.

4. Further results and conclusion

Policy advisors in the USA acknowledge the huge variety of factors that play a role as causes for obesity (e.g. Trust for America’s Health (TFAH), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Nemours et al). Policy documents and political debates reveal that there is no doubt in assessing and evaluating health inequity and its impact on obesity. Furthermore, policy-makers can be aware of the role the food and beverage industry plays and cannot ignore how severely the industry’s marketing strategies influence people, especially children, since that issue is comprehensively documented (reports of TFAH 2009, 2016, 2019). Generally, the social and environmental determinants of health – in this case all issues creating an “obesogenic environment” (Walls et al 2011) – are publicly acknowledged (see for example Senate Hearing 111-1130, 2010).

There is a huge amount of policy documents, reports and studies from governmental and non-governmental actors which are all based on sophisticated and unambiguous documentations, stressing the relevance of social determinants of health and underlining the need for complex approaches. However, it is precisely that large group of non-or semi-governmental actors who dominate the critical debate and who disclose lots of information about the complex interaction of factors promoting obesity. The phenomenon of childhood obesity and health inequity dominates the discourse at state and federal level in the US as the major issue. Reports and studies undoubtedly communicate how severe external effects influence people’s health and their (un)healthy behaviors. Hence, obesity is neither claimed as being a result of individual behavior as such, nor of people’s unwillingness or lack of discipline, but largely acknowledged as a complex economic and societal issue.

As a conclusion, we see that there is a diverse array of social determinants which explain the prevalence of obesity at the individual and at population level. On the meta-level (population) there is no doubt that obesity is caused primarily from environmental factors: access to healthy food, food prices (processed food versus with high sugar content versus healthy choices, fresh food etc.) or the walkability of living environments. Acknowledging this would mean to shift at least part of the responsibility from the individual towards the collective. However, if building-up infrastructure to increase physical activity or if introducing some (informational) programs at schools or if building committees on community level can really solve the problem, is open to question. This is not to say, that such policies are not necessary, however, they could be chosen as a “fig leaf” so as not to have to regulate stricture, more intrusive – especially with regard to the food and beverage industry that is involved in offering products which have an impact on people’s health and weight.

The US case shows that specific, sustainable and especially “culturally-tailored” interventions are necessary (Wang et al 2020). Probably, the examples from the US could give an idea what is important for Germany and also for states like NRW: A cultural, socio-demographic and socio-economic diverse population would also call for appropriate policies which are suitable for managing complexity. We learn from the example that since there are different groups of addressees it needs a complex strategy of combining policies – keeping in mind that addressing specific target groups (e.g. food industry, famers) is a highly political issue. The huge spectrum of policies observed in the US show that different and often contradictory fields of policymaking are concerned. Furthermore, we know from the literature that there is disputed and complex evidence explaining causes and effects with regard to obesity. All examples from the US confirm that policy instruments in this field are in general less coercive (few bans and orders, potential for conflict when it comes to taxes). However, there could be hard effects if soft tools are applied and used as a sign towards market actors to change strategies voluntarily (shadow of hierarchy). The fact that policy instruments informed by behavioral science are (rarely or) not found could be surprising seeing that there is much theoretical and scientific literature in behavioral science using examples from health policy. Generally, we can observe a political “loading“ of scientific evidence which is (partly) in line with fear of paternalism. This might be one reason why behaviorally informed policy instruments play a less prominent role in obesity policies so far.

The prevalence of obesity challenges public policy. Even if one said that this “battle could never be won”, there is rising national and international awareness and no chance to shut the eyes and do nothing. Managing complexity seems to be more realistic than solving a problem. National governments and subnational political actors – like in NRW – will have to deal with five major challenges in the future if they decide on targets to reduce or at least stabilize the number of people have obesity: First, policymakers would always have to find instruments that are suited to manage complexity. A limited focus on obesity as a “health issue” would not do justice to the fact, that cross-sector policy-making is absolutely necessary. Agricultural, economic, social, consumer, and health policy have to be connected. Second, policymakers need to solve the problem of knowledge transfer, they have to find ways to translate public health recommendations into policies, and they must simultaneously answer the question how to handle disputed evidence (with regard to obesity / NCDs). Third, the on-going (and probably major) challenge are the power resources of veto-players. On the one hand, this has to do with the characteristics of a cross-sector policy issue, and on the other hand, there is the very general conflict of the freedom of choice and markets (producers and consumers) and the need for regulation (marketing, advertising, ingredients of processed food etc.). Furthermore, major players (multinational companies and their massive market penetration) are actors in globalized capitalist society and economies which gives them a huge influence on all political levels. Fourth, no less difficult to deal with is the influence of (political) culture and societal rituals that play a major role when it comes to food and drinking habits, sedentary behaviour etc. And fifth, seeing epidemiological data and acknowledging the relevance of obesogenic environments and socio-economic factors it would be necessary to develop social policies that effectively counteract this societal and collective problem by giving people a different basis for shaping their daily lives.

References

Akil, L., and H Anwar Ahmad, H A, 2011, Effects of socioeconomic factors on obesity rates in four southern states and Colorado. Ethnicity & disease vol. 21,1, pp. 58-62.

Béland, D., Howlett, M., & Mukherjee, I. (2018). Instrument constituencies and public policy-making: An introduction. Policy and Society, 37(1), pp. 1-13.

Blüher, M., 2019, Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nature Reviews Endocrinology volume 15, pp. 288–298.

Daviter, F., 2007, Policy framing in the European Union. Journal of European public policy, 14 (4), pp. 654-666.

Hood, C. C., 2007, Intellectual Obsolescence and Intellectual Makeovers: Reflections on the Tools of Government after Two Decades. Governance, 20(1), pp. 127–144.

Hood, C C. and Margetts, H Z., 2007, The tools of government in the digital age (Basingstoke: Palgrave).

Howlett, M., 2011, Designing Public Policies: Principles and Instruments (New York: Routledge).

Howlett, M., 2019, Dealing with Colatile Policy Mixes: Spill Over Effects, Maliciousness and Gamesmanship in Policy Designs and Designing. Unpublished Manuscript.

Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A., 1979, Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica, 47 (2), pp. 263–292.

Kahneman, D., 2011, Thinking, fast and slow (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux).

Kroll, L E., and Lampert, T., 2010, “Regionale Unterschiede in der Gesundheit am Beispiel von Adipositas und Diabetes mellitus.” Robert Koch-Institut, editor. Daten und Fakten: Ergebnisse der Studie» Gesundheit in Deutschland aktuell: pp. 51-59.

Linder, S. H., and Peters, B. G., 1984, From social theory to policy design. Journal of Public Policy, 4(3), pp. 237-259.

Loer, K., 2019, The enzymatic effect of behavioural sciences: what about policy-makers’ expectations?, in: Straßheim, H. and Beck, S. (Eds) Handbook of Behavioural Change and Public Policy, (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), pp. 180-194.

Mello, M. M., Studdert, D. M., and Brennan, T. A., 2006, Obesity – the new frontier of public health law. The New England Journal of Medicine, 354(24), pp. 2601-2610.

Musingarimi, P., 2009, Obesity in the UK: a review and comparative analysis of policies within the devolved administrations. Health policy, 91(1), pp. 10-16.

Peters, B. G., 2018, Policy Problems and Policy Design (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing).

Peters, G. B., 2005, The problem of policy problems. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 7(4), pp. 349-370.

Reisch, L. A., and Zhao, M., 2017, Behavioural economics, consumer behaviour and consumer policy: state of the art. Behavioural Public Policy, 1(2), pp. 190-206.

Robert Koch-Institut (ed.), 2015, Gesundheit in Deutschland. Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. Gemeinsam getragen von RKI und Destatis. RKI, Berlin.

Salamon, L. M., 1981, Rethinking public management: Third-party government and the changing forms of government action. Public policy, 29(3), pp. 255-275.

Schienkiewitz, A, et al. 2017, Übergewicht und Adipositas bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland.

Schneider, A., and Ingram, H., 1990, Behavioral assumptions of policy tools. The Journal of Politics, 52(2), pp. 510-529.

Shugart, H. A., 2016, Heavy: The obesity crisis in cultural context (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Vedung, E., 2010, Policy instruments: typologies and theories, in: Bemelmans-Videc, M.-L., Rist, R. C. and Vedung, E. (Eds) Carrots, sticks & sermons. Policy instruments and their evaluation (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers), pp. 21-58.

Walls, H.L., Peeters, A., Proietto, J., 2011, Public health campaigns and obesity – a critique. BMC Public Health 11, 136. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-136

Wang, Y, Beydoun, MA, et al 2020, Has the prevalence of overweight, obesity and central obesity levelled off in the United States? Trends, patterns, disparities, and future projections for the obesity epidemic, International Journal of Epidemiology, dyz273, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyz273.

Yusuf ZI, et al 2010, Social Determinants of Overweight and Obesity Among Children in the United States. Int J MCH AIDS. 2020;9(1):22‐33. doi:10.21106/ijma.337.

Reference:

Loer, Kathrin (2020): Obesity as a policy problem: Managing complexity or solving the problem?, On the (missing) interconnectedness between food, health and consumer politics in the United States, Research Report, Published online at: regierungsforschung.de. Available online: https://regierungsforschung.de/obesity-as-a-policy-problem-managing-complexity-or-solving-the-problem/

This work by Kathrin Loer is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

- This research report makes use of the results of work made possible thanks to the Fellowship at the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies (AICGS) – this includes extensive research, background discussions, and some expert interviews, which for this report are supplemented by some previously conducted interviews. I am extremely grateful to the state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the NRW School of Governance for making the research stay in Washington, D.C. possible. [↩]

- Following the WHO, obesity is defined as “excessive fat accumulation that might impair health and is diagnosed at a BMI ≥30 kg/m2” (Blüher 2019, p. 288). Compare FN 3. [↩]

- For an overview of further limits of the behavioral spin see Loer 2019, 190. [↩]

- Principally, we can assume that it is politically challenging to decide in favor of less intrusiveness or coerciveness since that would be politically less risky inmost settings. In contrast to such a strategy of “soft regulation”, policy-makers could increase the chances of success by using forms of more intrusive of coercive instruments. [↩]

- The following paragraphs refer to the data of the “Centers for Disease Control and Prevention” (CDC). Data is available for the years 2011 to 2018. Using this data should give an impression of the dimension and dynamics the phenomenon of obesity (and overweight as preliminary stage often ending up in obesity. This report follows the definition of the CDC which is consistent with data from NRW (Germany): “Obesity is defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30.0; BMI was calculated from self-reported weight and height (weight [kg]/ height [m²).” (https://nccd.cdc.gov/, 20/05/02). [↩]

- The selection of US states is neither intended to be a systematic comparison nor is are these comparative cases with regard to NRW. It is a matter of first presenting and classifying different political strategies in order to draw a picture of the problem structure and of typical political approaches to dealing with the phenomenon of obesity. [↩]

- For state figures please select the state in the drop-down menu. [↩]

- Interestingly, there is no regular updating of figures neither for NRW nor for Germany in general. There are some studies that are referring to old(er) data, so far, the prevalence of obesity and overweight is not continuously monitored. [↩]

- The CDC dataset contains policy data (CDC Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity Legislation) for 50 US states and DC from 2001 to 2017 (https://chronicdata.cdc.gov/Nutrition-Physical-Activity-and-Obesity/CDC-Nutrition-Physical-Activity-and-Obesity-Legisl/nxst-x9p4, 20/05/14). CDC data is used exploratively in order to get an idea of the spectrum of policy instruments in the years after 2000. If the presentation were to go beyond this and if it wanted to make superordinate statements, the data set would have been evaluated in a different way – additional data and information would have to be included. Database errors could exist, especially in terms of categorization and completeness. [↩]

- The CDC lists a total of 416 policies for Colorado, including 108 from the category „dead“, i.e. not effective. [↩]

- For New York (state), CDC records a total of 3332 policy actions in the period 2001-2015. Of these, 798 have entered into force or been introduced. 40 measures have been vetoed, the remaining 2493 are registered as “dead”. [↩]

- CDC reports on 223 policies between 2002 and 2015 of which 84 were enacted / introduced and all others (138) “dead” or vetoed (1). [↩]

- The findings from the data analysis were discussed with experts in order to evaluate how the choice of instruments could be classified and explained. This research reports focuses on the classification and systematization of instruments and the question who is mainly addressed. It will be followed by publications that concentrate on the underlying political factors that drive certain instrument (non-)choices. [↩]